On January 28, 1986, the U.S.A. experienced a tragedy that has since faded into history. If you weren’t yet born at that time, you may not have even heard of it. I remember talking about the space shuttle to a classroom full of junior high students in the late 90s where I was blindsided by a young man who asked whether one had ever blown up. That something indelibly imprinted on my memory could be unknown to someone, even an adolescent, was incredible. Until I realized the simple fact that the kid hadn’t been born yet.

Wow. To me it felt as if it had occurred the day before.

I was a physics major in college with aspirations to work in the aerospace industry. The day we lost the space shuttle, Challenger, for me was a very bad day. Ironically, that’s exactly what NASA calls such an event, a “bad day.” Well, no shit.

Sorry, I usually avoid naughty words in my blogs, but in that context my expansive vocabulary entirely fails me. Somehow nothing defines NASA’s understatement of tragedy as well as an expletive. And much of why I feel that way is because, subsequent to the Challenger accident, I went to work at NASA as a contractor, ultimately winding up in their Safety Division, which meant I was privy to all sorts of dirty little secrets.

When I arrived at Johnson Space Center in Houston in April 1988, the agency was deep into what they referred to as “return to flight”; RTF in NASAspeak, given their propensity for acronyms. RTF comprised the time while they finished investigating the cause and put together design fixes to avoid a similar occurrence in the future, eventually getting back to what NASA did, i.e., send men and women into space. It’s interesting to consider that we didn’t even refer to it as Challenger; it was 51-L, the ill-fated flight’s official designation, which was less emotionally charged than calling it by name.

When I went to work in the Safety Division at Johnson Space Center in 1990, “The Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident” was required reading. This well-written document covered the technical details in a way that even my teen-aged son at the time could understand. I remember him reading it in the backseat of the car during a road trip. That same copy still resides on a shelf in my home office, bristling with numerous sticky notes and highlights marking the parts that struck me the most. But those are but tips of the proverbial iceberg.

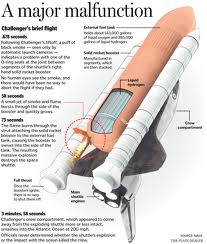

As anyone who’s actually familiar with the accident knows, its official cause related to the o-rings in the solid rocket booster which didn’t seal, allowing hot gasses to strike and penetrate the external fuel tank, which resulted in a deadly explosion. A major contributor to o-ring failure was the fact the launch took place when the temperature at Cape Canaveral in Florida was a mere 28 degrees F. This had never before been attempted, Floridian temperatures usually far above that range, even in January. This factor was illustrated dramatically by physicist Richard P. Feynman, a member of the investigation committee, by dropping an o-ring in a glass of ice water to demonstrate how they became brittle and incapable of performing their function at low temperatures.

As anyone who’s actually familiar with the accident knows, its official cause related to the o-rings in the solid rocket booster which didn’t seal, allowing hot gasses to strike and penetrate the external fuel tank, which resulted in a deadly explosion. A major contributor to o-ring failure was the fact the launch took place when the temperature at Cape Canaveral in Florida was a mere 28 degrees F. This had never before been attempted, Floridian temperatures usually far above that range, even in January. This factor was illustrated dramatically by physicist Richard P. Feynman, a member of the investigation committee, by dropping an o-ring in a glass of ice water to demonstrate how they became brittle and incapable of performing their function at low temperatures.

I lived in Northern Utah at the time of the accident, the manufacturer of the solid rocket boosters (a.k.a. SRBs), Morton Thiokol, located a few dozen miles away. Anyone who lives in such a climate is more than aware of the effects of cold weather. As I recall, the SRBs had never been tested in that temperature range, either.

On the surface, it appears that this tragic accident that claimed the lives of seven astronauts, including teacher Christa McAuliffe, took everyone by surprise. But in reality, as I learned working in Safety for nearly 20 years, it was processes and politics every bit as much as faulty design. They knew; they just ignored it. The true cause was as elusive as missing shuttle pieces still on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. [NOTE:–If you’re interested in more sordid details about the Dark Side of NASA, I recommend “Challenger: A Major Malfunction” by Malcolm McConnell or “Prescription for Disaster” by Joseph Trento.]

Anything that can cause a problem, either critical or catastrophic, is documented on a Hazard Report, with o-ring leakage no exception. Hazard Reports (HRs) contain causes along with controls, though some hazards are simply classified as an “accepted risk” if there’s nothing that can be done to prevent them. Space flight is risky and there are some things you simply can’t avoid or control; bird strikes and meteorites come to mind.

O-ring failure was a catastrophic hazard and documented as such. That the design was faulty was likewise known. Engineers had seen leakage on previous flights. Let that sink in for a moment. O-ring failure had happened before. However, earlier instances had not caused an accident. This resulted in a very dangerous and ultimately fatal thought pattern that led them to believe that perhaps it wasn’t as serious as they thought. Previous failures had been investigated, the leakage referred to as “blow-by” and eventually accepted as not a safety issue.

O-ring failure was a catastrophic hazard and documented as such. That the design was faulty was likewise known. Engineers had seen leakage on previous flights. Let that sink in for a moment. O-ring failure had happened before. However, earlier instances had not caused an accident. This resulted in a very dangerous and ultimately fatal thought pattern that led them to believe that perhaps it wasn’t as serious as they thought. Previous failures had been investigated, the leakage referred to as “blow-by” and eventually accepted as not a safety issue.

How wrong they were. In reality, they were playing Russian Roulette. Just because they got away with it a few times did not mean it wasn’t a hazard, only that they’d dodged a bullet. A Thiokol engineer named Roger Boisjoly had written a memo before the accident pointing out the seriousness of the problem. It was essentially ignored, most likely for budget and scheduling reasons. Unfortunately, his sordid prophecy of impending disaster was fulfilled almost exactly six months later. Later, to cover their sins, Morton Thiokol and NASA decimated Mr. Boisjoly, typical behavior employed to discredit whistleblowers.

I’d like to point out that for many accidents the public sees Safety as the culprit. Wasn’t it safety’s job to prevent such a horrific occurrence? Yes, it certainly was. And I must say that we did everything possible to assure safety of flight. We were the ones who made sure all risks and hazards were properly controlled and documented. This more refined process, however, was instituted after and because of the Challenger accident. The full rigor of the safety process recommended post 51L by the Presidential Commission was never fully instituted, however. A plethora of subsequent reorgs were supposed to make safety more of a priority, yet somehow eroded, as proven by the Columbia disaster 17 years later. An accident which has a strikingly similar administrative postmortem.

If you remember the movie, “Deep Impact,” you might recall the line where the female member of the crew on that fictitious shuttle flight, charged with protecting our planet from a collision with an approaching asteroid, noted that if they died in service to their country that all they’d probably get was a high school named after them, which is more truth than poetry. So let’s take a moment to remember those seven brave individuals by name who died so needlessly 30 years ago. They represented different genders, races and ethnicities, some professional astronauts, others not.

Francis R. (Dick) Scobee (Commander)

Michael John Smith (Pilot)

Ronald Erwin McNair (Mission Specialist)

Ellison S. Onizuka (Mission Specialist)

Judith Arlene Resnik (Mission Specialist)

Christa McAuliffe (Payload Specialist & school teacher, winner of the “Teacher in Space” competition)

Gregory Bruce Jarvis (Payload Specialist & aerospace engineer, bumped to this flight by a U.S. Senator who took Greg’s original spot)

As they say, those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it. And repeat it they did, within four days of being exactly 17 years later on February 1, 2003 when we lost Columbia.

Watch for more on that tragedy on the 13th anniversary of that disaster.

4. NASA has definitely been known to blow up rockets, not only in the early days of the initial space race with Russia to get to the Moon in the late 50s and 60s, but even more recently as many of you may recall with the Space Shuttle Challenger accident on January 28, 1986. Private rocket companies more recently are having a similar problem. Rocket fuel is highly volatile, systems complex, and problems are inevitable. Thus, when the rocket they put together in record time to send supplies blew up it wasn’t much of a stretch. Anyone who didn’t see that one coming hasn’t been paying attention to the space industry and its explosive history (pun intended).

4. NASA has definitely been known to blow up rockets, not only in the early days of the initial space race with Russia to get to the Moon in the late 50s and 60s, but even more recently as many of you may recall with the Space Shuttle Challenger accident on January 28, 1986. Private rocket companies more recently are having a similar problem. Rocket fuel is highly volatile, systems complex, and problems are inevitable. Thus, when the rocket they put together in record time to send supplies blew up it wasn’t much of a stretch. Anyone who didn’t see that one coming hasn’t been paying attention to the space industry and its explosive history (pun intended).